Fearing the scorching Texas heat could only get worse, Lisa Vogt stopped buying meat and drove her pickup truck as little as possible to save money for two months to purchase window air-conditioning units.

The air conditioner at the home that Vogt, 32, her three children and teenage nephew rent in southeast San Antonio has been broken for several months.

At some point, Vogt gave her kids cups of ice to chew or popsicles all day long, hoping it would help them cool their bodies.

“I couldn’t let any of my kids suffer in this heat,” said Vogt, who makes a living selling custom T-shirts. The family couldn’t wait any longer for their landlord to make repairs and purchased the units a couple of weeks ago after dipping into money meant to pay their electric bill.

Millions of Americans have been living through a heat wave this week as parts of the West to New England see dangerously hot temperatures but many don’t have resources to weather it. Like Vogt, some people of color and low-income communities may not have access to cooling and if they do, many cannot afford the rising cost of energy.

Triple-digit temperatures have been reported in parts of California, Texas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and Tennessee this week, and meteorologists estimate that more than 85% of the population – or 275 million Americans – could see high temperatures above 90 degrees over the next week.

To avoid the distressing heat and its potential health risks, officials in multiple cities are encouraging residents to stay indoors in air-conditioned spaces. But that’s not an option for Americans who work in agriculture, construction and for those who can’t afford the cost of the electricity needed to power cooling units.

In Texas, where temperatures have reached more than 105 degrees this week, the cost of electricity was “beyond affordable” for most low-income households. On average, families spend about 8% of their income on energy expenses, said Andrew Robison, a research analyst with the Texas Energy Poverty Research Institute.

Kayla Miranda, a housing advocate who lives in San Antonio’s oldest and largest public housing project, Alazan-Apache Courts, with her children, said many of her neighbors are constantly forced to decide between paying for electricity, food, gas or medicines because they can’t afford to cover everything with their income.

Miranda says she pays about $350 a month for electricity when the city sees triple-digit temperatures. The three window air-conditioning units in her 789-square-feet apartment are only able to cool the rooms to about 80-85 degrees.

“That’s the most of these little units can handle and they’re running over time,” said Miranda, adding that the complex where she lives has not had A/C installed since it was built in the 1930s.

“We have tenants that are choosing to not turn on the A/C so that they can still pay their rent and not be homeless. Or they’re choosing take their medicine over having air conditioning and that should never be the case,” Miranda added.

The so-called urban heat island effect

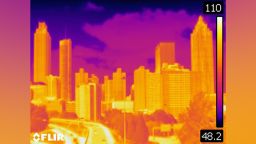

In Texas, there is no state law that requires landlords to provide air conditioning in a rental home or apartment. However, state property law indicates a landlord shall fix a hazardous condition impacting their tenant’s health or safety, including cooling. A recent study from the University of California, San Diego, found that low-income neighborhoods and communities with high Black, Hispanic and Asian populations experience significantly more heat than wealthier and predominantly White neighborhoods.

This is because of the so-called urban heat island effect, which has made some urban communities even more vulnerable. Areas with a lot of asphalt, buildings and freeways tend to absorb a significant amount of the sun’s energy and emit it as heat. Areas with green space — parks, rivers, tree-lined streets — absorb and emit less.

Miranda has seen the urban heat island effect in her neighborhood. A few weeks ago, she says, her brother walked with her 5-year-old son to a convenience store a block away.

“My poor little boy came back with his face so red. He came in and he just sat on the couch for like an hour. He did not move and I’ve never seen that before,” she says.

With heat being one of the top weather-related causes of death in the US, authorities across the nation are urging residents to prioritize being in air-conditioned spaces to avoid any heat-related illnesses.

In Arizona’s Maricopa County, there have been 29 confirmed heat-associated deaths during the 2022 heat season with the first death reported on March 13, according to the county’s public health department.

Of the 29 deaths, there have been six deaths that took place indoors, including one in which there was no air conditioning, one where the air conditioning was not working and one where the cooling unit was not in use, according to a report by the health department.

Last month, health officials in New York City published a report examining the deadly impact of heat in recent decades. Health officials said many of the deaths directly caused by heat occurred at home and a significant number did not have an air conditioner or one was either not working or not in use.