Each year, extreme temperatures take 5 million lives, while 400,000 people die from climate-related hunger and disease and scores perish in floods and wildfires.

Now, researchers are promoting a new legal theory that says fossil fuel companies – which, data show, are the leading contributors to planet-heating pollution – could be tried for homicide for climate-related deaths.

The radical idea, first proposed last year by consumer advocacy non-profit Public Citizen, may sound far-fetched, but it’s gaining interest from experts and public officials.

“We’ve been really excited to see the curiosity, interest and support these ideas have garnered from members of the legal community, including from both former and current federal, state and local prosecutors,” said Aaron Regunberg, senior policy counsel with Public Citizen’s climate program.

The Public Citizen researchers are currently holding events at top law schools including Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, Harvard, University of Chicago and New York University to promote the idea.

“I strongly support the effort to go after these bastards,” Christopher Rabb, a Pennsylvania state representative said at a recent UPenn event. The researchers say other public officials have expressed interest behind the scenes as well.

The proposal, which will soon be published in the Harvard Law Review, stems in part from the growing body of evidence that the fossil fuel industry hid information about the dangers of fossil fuel use from the public. Those revelations have inspired 40 lawsuits alleging big oil has violated tort, product liability and consumer protection laws and engaged in racketeering.

In addition to those civil lawsuits, fossil fuel companies should also face criminal charges, the researchers say.

“Criminal law is how we say what is right and wrong in our society,” said David Arkush, who directs Public Citizen’s climate program and co-authored the paper on the proposal. “I think it’s important that some of the most damaging conduct in human history be squarely recognized and pursued as criminal.”

There are a range of statutes that could criminalize fossil fuel companies’ climate conduct, the researchers say. Many of the civil claims facing oil companies, such as conspiracy and racketeering, have criminal counterparts, and other laws could be used to criminalize conduct that could inflict future harms, such as reckless endangerment. But the claim that could capture the sector’s gravest harms, the researchers say, is homicide.

Because oil companies fought to delay climate action despite knowing about global warming, there is a case to be made that they committed reckless or negligent homicide, according to Public Citizen.

“It’s well within the four signposts of the law that you ought to be able to bring one of these cases,” said Arkush. “We’ve talked to dozens of criminal law professors across the country, we’ve talked to former prosecutors, former department of justice prosecutors, and no one really has anything to say about us being wrong on the law.”

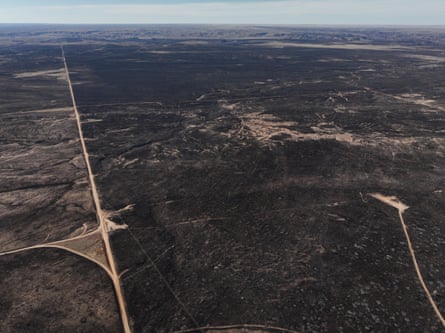

Energy companies have been charged with homicide for environmental crimes before, Arkush noted. California prosecutors charged the utility PG&E with manslaughter after a tree fell onto an aging transmission line and sparked a deadly 2018 wildfire in Paradise, California. Federal prosecutors also charged oil company BP with manslaughter after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster, which killed 11 workers and resulted in the largest oil spill in the history of marine oil-drilling operations. Both companies pleaded guilty and paid billions of dollars in penalties and fines.

Cindy Cho, a former Department of Justice prosecutor, said she was initially skeptical about Public Citizen’s proposal, which is called Climate Homicide: Prosecuting Big Oil for Climate Death.

“But once I read it, I thought that it was more compelling than I had guessed it would be,” she said.

Though she now believes it could be a “viable avenue for prosecution”, the legal proposal is not a slam dunk, said Cho, now a professor at Indiana University’s Maurer school of law. Even if a district attorney or attorney general is willing to bring such charges against some of the world’s most powerful corporations, that prosecutor would need significant resources and a highly specialized team, she said.

“You need people who understand the science on the prosecution team, in addition to people who understand a homicide prosecution, in addition to people who understand big, document-intensive white-collar prosecutions,” she said. “That’s not an easy team to assemble.”

Another challenge: though bringing charges of reckless or negligent homicide would not technically require plaintiffs to demonstrate oil companies killed with intent, in practice that’s something many prosecutors and jurors will look for, she said.

Demonstrating causality between an oil company and any single climate-related death would also likely prove difficult, she said. When a person dies in a hurricane, even if attribution science shows climate change was a factor in increasing the severity of the storm, a court would also have to consider other factors that exacerbated the risk they faced, such as the victim’s underlying health conditions or the strength of their home.

after newsletter promotion

“You could probably sit here for an hour and think of all of the factors,” she said. “And that’s before you even get to the knotty … question of showing that climate change led to the hurricane, that nothing else besides the actions of the company that lead to climate change was a cause.”

The researchers note that some criminal charges can be brought even without a demonstration of causality. Pennsylvania, for instance, has a criminal statute against not only causing, but also risking, catastrophe.

Even so, there are political and cultural barriers to filing novel charges against such well-heeled companies, the researchers say. But if such criminal litigation were successful, it could have major consequences for fossil fuel companies, potentially forcing the sector to alter how it operates.

Researchers point to the case of Purdue Pharma, which in response to federal charges over its role in the opioid crisis, accepted a 2020 settlement requiring it to restructure as a public benefit corporation focussed on delivering safe drugs and abating addiction. A similar settlement with oil companies could require them to focus on accelerating the clean energy transition and redressing past harms, the researchers say.

The proposal also represents a chance to “more accurately portray what a criminal looks like”, Cho said at the researchers’ UPenn event last week. While criminal law often targets individuals, many prosecutors are interested in going after “big defendants” who create structural harm, she said.

“I think that prosecutors should actively consider pursuing the theory, especially if they walk into the investigation with an understanding of the intense challenges,” she said.

Larry Krasner, the district attorney of Philadelphia, said in an email his office will “explore legal avenues by which we may seek accountability from polluters”.

Nikil Saval, a state senator from Pennsylvania, said the proposal captured his curiosity. “Fossil fuel companies and the executives that lead them … have committed crimes that have harmed the people of Pennsylvania and they should be held accountable for them,” he said.

Marian Ryan, the district attorney for Middlesex, Massachusetts, said it is “imperative that we acknowledge the profound impact of pollution and chemical exposure on individuals’ well-being.

“I look forward to learning more about this research as we continue our collective efforts to address the intersection of public health and safety,” she said of Public Citizen’s proposal.

Richard Wiles, president of the Center for Climate Integrity, which has supported civil suits against big oil, said the new theory “makes clear that efforts to hold the oil majors accountable are only beginning, and that lawyers will continue to pursue innovative legal strategies until the oil majors are finally held accountable for the massive harms they have caused”.

Sharon Eubanks, who was lead counsel on behalf of the US in the successful 2005 legal action against big tobacco, said she is supportive of the new theory and noted that her plan to sue big tobacco faced similar skepticism.

“There were a lot of people who said we were crazy to charge big tobacco with racketeering and that we could never win,” she said. “But you know what? We did win. I think we need that same kind of thinking to deal with the climate crisis.”