There is a universe in which Hurricane Sandy didn’t create quite so much devastation back in 2012; where the waters, which surged deep into subway tunnels and left parts of New York City in the dark for days, left some parts of the tri-state area unscathed.

And that universe, according to scientists, is one without climate change.

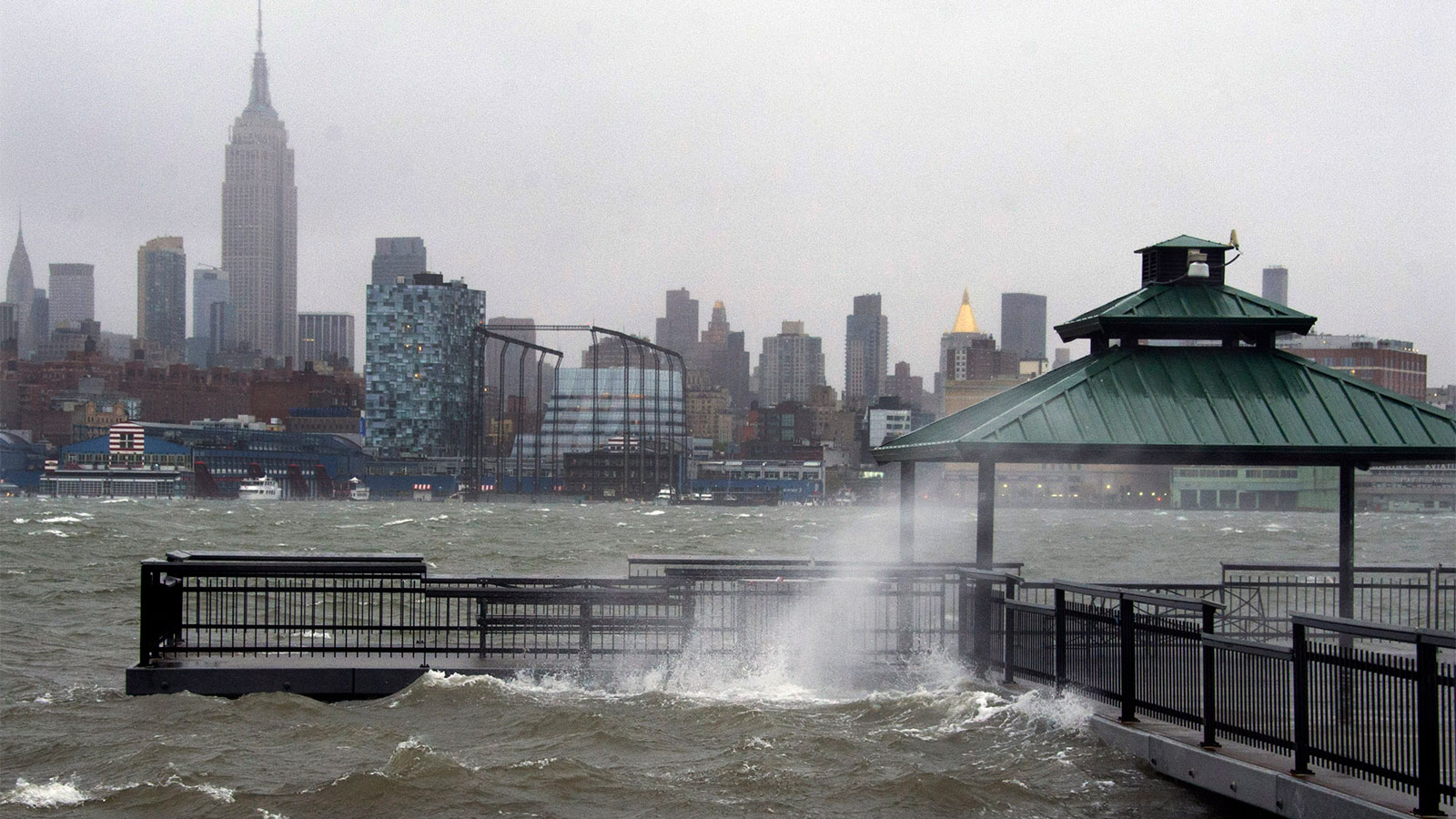

Superstorm Sandy destroyed half a million homes, killed 159 people, and caused $62.5 billion in damages. And, according to a new study out Tuesday in Nature Communications, 13 percent of its costs can be attributed to human-caused sea-level rise. In other words, without warming temperatures and rising seas, tens of thousands of homes would have gone untouched, and $8.1 billion of damages would not have occurred.

“Climate change is already hurting us much more than we realize,” said Benjamin Strauss, chief scientist at the research and communications nonprofit Climate Central and one of the study’s authors. (Strauss was also once a member of Grist’s board of directors.)

Linking climate change to disastrous weather events like droughts, hurricanes, or floods is always tricky: Terrible storms happened before people started mucking with the global thermostat, and they’ll continue even if countries start to get their emissions under control. But scientists have long said that warming temperatures can make certain types of weather — heat waves, severe droughts, and floods — more likely or more severe.

Nine years after Sandy made landfall, though, scientists still aren’t positive if the fourth-costliest hurricane in U.S. history was made more likely by warming temperatures. So Strauss and his co-authors took a different tack. Instead of investigating whether warmer temperatures affected the likelihood of the hurricane itself, they focused on whether the damage done by Sandy — the homes flooded in New York City or the piers destroyed in New Jersey — had been made worse by human-caused sea-level rise.

To do so, researchers simulated two different universes: One with the higher sea levels brought on by human carbon emissions and one without. First, they analyzed how much seas had risen in the New York area thanks to climate change. “When ice melts from glaciers or from Greenland, that water doesn’t get evenly distributed around the world like peanut butter on a piece of bread,” Strauss explained.

The scientists estimated that without human emissions of greenhouse gases, the sea level in the tri-state area would be about 4 inches, or 9.6 centimeters, lower than it is today.

They then used a giant simulation from the Army Corps of Engineers to model how Hurricane Sandy would have unfolded with lower sea levels, tracking how the water would have spilled into Manhattan, the Jersey Shore, and Long Island. Finally, the researchers took those results and deployed a Federal Emergency Management Agency model to estimate damages that flooding would have caused — and compared them to the damages simulated under actual sea levels.

Strauss and his co-authors found not only that sea-level rise brought on by humans was responsible for approximately 13 percent of Sandy’s damages, but also that without those four extra inches of water, around 71,000 people would not have been affected by Hurricane Sandy’s flooding at all. (The researchers did not attempt to account for any deaths caused by the storm.)

And that, according to Strauss, may actually be an underestimate. Thirteen percent was a mid-range approximation; the damages from sea-level rise, he said, could be as high as $14 billion (or as low as $4.7 billion).

Antonia Sebastian, an assistant professor of applied hydrology at the University of North Carolina who was not involved in the research, called the paper “exciting.” While other studies have attempted to link climate change to extreme flooding, she said, “This is one of the first papers I’ve seen that really takes it a step further and looks at what that means in terms of total damage.”

At the same time, Sebastian cautioned that it can be very difficult to model damages caused by flooding. The FEMA model that the researchers used, for instance, didn’t accurately simulate the $62.5 billion costs of Hurricane Sandy; in fact, Philip Orton, a research associate professor at Stevens Institute of Technology and another author of the recent paper, said that it underestimated the cost by a factor of six.

In some ways, that’s to be expected. The model only looked at the depth of flooding in residential and commercial buildings, and left out damages to infrastructure like subways or bridges. So, Orton said, researchers didn’t rely on the FEMA model to estimate the exact costs of Sandy, but instead used it as a “scaling factor” to compare the different possible damages with and without anthropogenic sea-level rise.

Still, the study is a good start for scientists looking to put a price tag on disasters brought on by warming temperatures, vicious hurricanes, and rising seas. Similar research could be used in court against oil companies. Maui County in Hawaii, Hoboken, New Jersey, and Charleston, South Carolina have already filed lawsuits against fossil fuel companies for damages from sea-level rise, as have several cities and counties in California.

Orton, who was living in New Jersey when Sandy hit, said that the research felt personal. “We had flooding within half a block of where we live,” he told me. “I saw firsthand how people’s lives were dramatically changed.”